There is a way to send more volume/sound your way without losing the volume of sound you are sending to others in the jam, cut a soundport.

This is a modification that cannot be undone, so you should probably not do this to your Martin unless you intend on NEVER selling it as it will lose resale value. In fact, if you decide to try this, you should probably try it on your Bennett acoustic first to see if it does as much as you would like.

Sound ports are quite common these days in the realm of high end boutique acoustic guitars. Even Martin is beginning to add soundports to their high end instruments.

The Martin CS-GP-14:

This idea behind the soundport is to throw more sound in the direction of the player (the tone is fuller and louder for the player) allowing the player to nuance the production of dynamics in a more knowing way. And it really works! When a soundport is properly cut, the player gets quite a bit more volume and the tone is richer/fuller than it would normally be from the players perspective. It sounds more like you are out in front of the instrument.

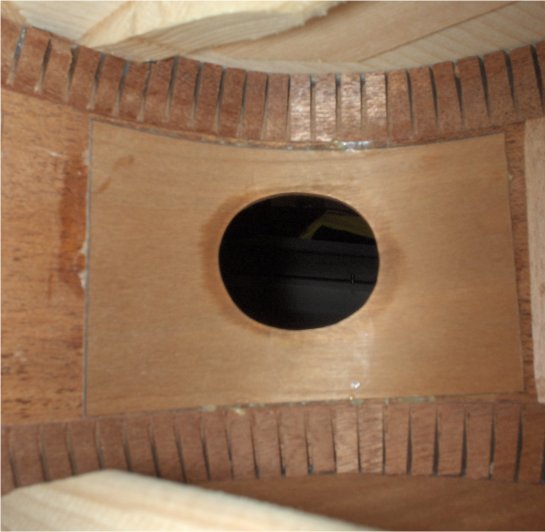

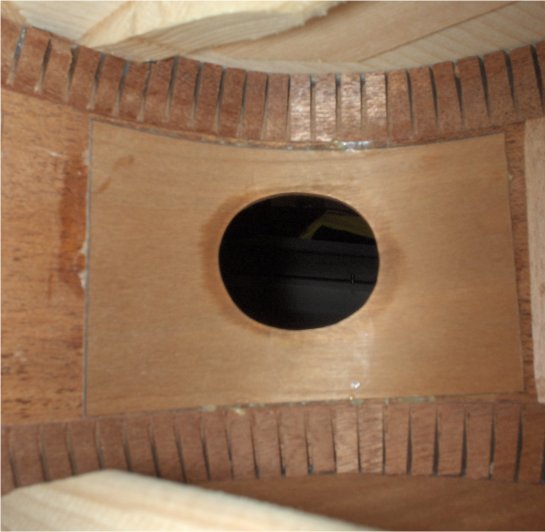

I have had the same problem as yourself. When playing with loud bluegrass instruments in a jam or performance setting, it tough to hear myself; a little like flying blind. So I decided to try and cut a soundport in my dreadnought. Cutting the hole is not that tough, a dremel works quite nicely. But I wanted to make sure that the guitar would not immediately crack where the hole was cut. So I took a very thin patch of mahogany laminate and glued it to the inside of the guitar where I was going to cut the hole. This would give support to the side and as the patch was a laminate, it would not contract and expand with changes in humidity.

I first needed to draw on the side approximately where I wanted the hole. It should point directly toward me so that I can hear as good as possible. I suggest that you do this with a light colored magic marker (silver will work) and play for a few days so that you are sure you have positioned the hole properly. After you have found the proper position, position the patch in the inside of the guitar centered where the hole will be.

This was glued with basic carpenters glue and I used neodymium magnets as clamps until the patch dried. *The discoloration near the soundhole is from stain used (after the hole was cut) to match the edge of the veneer to the edge of the wood on the guitar. *

Then I got out my dremel and went to town…  Actually, I called my wife in just as I was driving the dremel into the side of the guitar (I wanted to see her shocked look). I carefully stayed inside the line I had drawn on the outside of the guitar. I then changed the dremel cutter to the sanding tube and slowly cut the hole to a smooth oval.

Actually, I called my wife in just as I was driving the dremel into the side of the guitar (I wanted to see her shocked look). I carefully stayed inside the line I had drawn on the outside of the guitar. I then changed the dremel cutter to the sanding tube and slowly cut the hole to a smooth oval.

The result was wonderful. I can hear myself much better than before when playing with other loud instruments. Also, the guitar is just as loud as before out in front of me while it seems louder as you approach the instrument. Also, the tone from the players position is much fuller and nicer.

Various builders will build various types of soundports.

http://www.mcknightguitars.com/images/Img20.gif

http://www.andrewwhiteguitars.com/images/models/fine_details/content/bin/images/large/AWG_Flourette_33.jpg

https://www.stevehowell.ws/images/gallery/grandcabret/Grand_Cabaret_soundport.jpg

http://dreamguitars.com/products/applegate/applegate_sj_90/images/soundport.jpg

My suggestion is to make sure you mark the side of your guitar with a drawing of the soundport and live with it for at least a few days and make sure it is pointing directly at you. If the soundport is pointing more toward your right shoulder or left shoulder, move the mark to point directly at your face! I have since put three soundports in three of my acoustics with the first one I placed pointing too much toward my right shoulder. On that guitar, the soundport is by far the least effective.

Good Luck!

Actually, I called my wife in just as I was driving the dremel into the side of the guitar (I wanted to see her shocked look). I carefully stayed inside the line I had drawn on the outside of the guitar. I then changed the dremel cutter to the sanding tube and slowly cut the hole to a smooth oval.

Actually, I called my wife in just as I was driving the dremel into the side of the guitar (I wanted to see her shocked look). I carefully stayed inside the line I had drawn on the outside of the guitar. I then changed the dremel cutter to the sanding tube and slowly cut the hole to a smooth oval.

Eastman did make a fan fretted acoustic guitar with a soundport that listed for just about $3000 (almost affordable but not quite).

Eastman did make a fan fretted acoustic guitar with a soundport that listed for just about $3000 (almost affordable but not quite).